Orienteering: Great exercise and better thinking skills?

Picture this: you’re with friends in an unfamiliar forest using only a map and a compass to guide you to an upcoming checkpoint. There are no cell phones or GPS gadgets to help, just good old brainpower fueled by a sense of adventure as you wind through leafy trees and dappled sunlight.

This is not an excursion to a campsite or a treasure hunt. It’s a navigation sport called orienteering — a fun way to get outside, exercise, and maybe even help fight cognitive decline, according to a 2023 study.

What is orienteering?

Orienteering combines map and compass reading with exercise. Competitors (“orienteers”) race against a clock to reach checkpoints in outdoor settings that can range from city parks to remote areas with mountains, lakes, rivers, or snowy fields.

“You can go out in a group or on your own. You get a very detailed map and navigate your way to checkpoints that record your time electronically,” says Clinton Morse, national communications manager with Orienteering USA, the national governing body for the sport in the United States.

Because orienteers are racing the clock, they might run on trails, hike up hills, or scramble around boulders. That’s for foot-orienteering events. There are also orienteering events with courses geared for mountain biking, cross-country skiing, or canoeing.

How might orienteering affect thinking skills?

A small 2023 study published online in PLoS One found a potential link between orienteering and sharp thinking skills.

Researchers asked 158 healthy people, ages 18 to 87, about their health, activities, navigation abilities, and memory. About half of the participants had varying levels of orienteering experience. The other participants were physically active but weren’t orienteers.

Compared with study participants who didn’t engage in orienteering, those who were orienteers reported

- having better navigational processing skills (recognizing where objects were, and where participants were in relation to the objects)

- having better navigational memory skills (recalling routes and landmarks).

The study was observational — that is, not a true experiment — and thus didn’t prove that orienteering boosted people’s thinking skills. But the link might be plausible.

“Aerobic exercise releases chemicals in the brain that foster the growth of new brain cells. And when you use a map and connect it to landmarks, you stimulate growth between brain cells,” says Dr. Andrew Budson, lecturer in neurology at Harvard Medical School and chief of cognitive and behavioral neurology at VA Boston Healthcare System.

Where can you find orienteering opportunities?

There are about 70 orienteering clubs across the United States, and many more around the world (the sport is extremely popular in Europe). To find an orienteering event in your area, use the club finder tool offered by Orienteering USA.

How can you get started with orienteering?

People of all ages and athletic levels can take part, because orienteering courses vary from local parks to wilderness experiences. Costs are about $7 to $10 per person for local events, or $25 to $40 per person for national events, plus any travel and lodging expenses.

To make orienteering easy at first, Morse suggests going with a group and taking things slowly on a short novice course. “You don’t have to race,” he says. “Some people do this recreationally to enjoy the challenge of completing a course at their own pace.”

The trickiest part is learning to read the map. Morse’s advice:

- Turn the map as you change directions. Hold the map so that the direction you’re heading in is at the top of the page. For example, if the compass indicates that you’re heading south, turn the map upside down, so the south part is on top and easier to follow.

- Create a mental image of what the map is telling you. If there’s a fence along a field on the map, build a picture of it in your mind so you can recognize it when you see it, even if you haven’t been there before.

Tips for safe and enjoyable orienteering events:

- Dress appropriately. Wear comfortable clothes including long pants, good walking shoes, and a hat.

- Lather up. You’ll be outside for at least an hour, and you’ll need sunblock and possibly tick and bug spray depending on the terrain. Preventing tick bites that can lead to Lyme disease and other tick-borne illnesses is important in many locations.

- Bring some essentials. Pack water, a snack, sunblock, bug spray, and your phone. (Keep the phone turned off unless you need to call for help.)

- Use good judgment. Know that the shortest route on the map won’t always be the best, since it might take you up a hill or through thick vegetation. It might be better to go around those areas.

Once you learn the basics of orienteering, you can make it more physically challenging (and a better workout) by going faster and trying to beat your previous times, or by signing up for a more advanced course that’s longer and requires more exertion and speed.

And no matter which event you take part in, enjoy the adventure. “You’re not just following a path, you’re solving puzzles while being immersed in nature,” Morse says. “It’s a great way to experience the outdoors.”

About the Author

Heidi Godman, Executive Editor, Harvard Health Letter

Heidi Godman is the executive editor of the Harvard Health Letter. Before coming to the Health Letter, she was an award-winning television news anchor and medical reporter for 25 years. Heidi was named a journalism fellow … See Full Bio View all posts by Heidi Godman

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Howard LeWine is a practicing internist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Chief Medical Editor at Harvard Health Publishing, and editor in chief of Harvard Men’s Health Watch. See Full Bio View all posts by Howard E. LeWine, MD

The cicadas are here: How’s your appetite?

You’ve probably heard the news: Cicadas are coming. Or — wait — they’re already here.

And are they ever! Due to an unusual overlap of the lifecycles of two types (or broods) of cicadas, trillions of cicadas are expected to emerge in the US by the end of June, especially in the Midwest.

If you’d like to see where they’ve already arrived, track them here. And if you’re wondering if this cicada-palooza could help with grocery bills, read on to decide for yourself how appealing and how safe snacking on cicadas is for you. The pros and cons could change your outlook on the impending swarm.

What to know about cicadas

Don’t worry, cicadas are largely harmless to humans. In fact, their appearance is welcome in places where people routinely snack on them as a low-cost source of calories and protein.

Estimates suggest up to two billion people regularly eat insects, especially in South and Central America, Asia, Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. Cicadas, when available, are among the most popular. And if you thought no one in the US eats cicadas, check out this video from a May 2024 baseball game.

Are you tempted to eat cicadas?

For plenty of people, cicadas aren’t the food of choice. Some people can’t get past the idea of eating insects as food. That’s understandable: after all, the culture in which we are raised has a powerful influence on what we consider acceptable in our diets. Something some Americans might find off-putting (such as eating snakes) is common in China and Southeast Asia. Meanwhile, people outside the US find aspects of the typical Western diet unappealing (such as root beer, peanut butter and jelly, and processed cheese).

But some people shouldn’t eat cicadas because it could be dangerous for them.

Why you should — or shouldn’t — eat cicadas

Eating cicadas is common in many parts of the world because they are

- nutritious: cicadas are low in fat and high in protein, including multiple essential amino acids

- inexpensive or free

- tasty (or so I’m told): descriptions of their flavor vary from nutty to citrusy to smoky and slightly crunchy.

In years when cicadas emerge, recipes for dishes containing cicadas emerge as well.

Then again, there are several good reasons to avoid making cicadas a part of your diet, including these:

- You just can’t get past the “ick” factor. Adventurous eaters may be willing to try or even embrace consuming cicadas, while others will be unable to view the idea as anything other than horrifying.

- You find the taste or consistency unappealing.

- You’re “cicada intolerant.” Some people get stomach upset, nausea, or diarrhea if they eat too many cicadas.

- You’re pregnant or breastfeeding, or are a young child. Concerns about even low levels of pesticides or other toxins in cicadas have led to recommendations that these groups not eat them. Doesn’t this suggest the rest of us should also steer clear? Well, thus far, at least, there’s no evidence that toxins in cicadas are causing health problems.

But there is one more very important entry on this list: people with a shellfish allergy should not eat cicadas. Odd, right?

The shellfish-cicada connection

Cicadas are biologically related to lobsters, shrimp, crabs, and other shellfish. So if you’re allergic to shellfish, you might also be allergic to cicadas. A particular protein called tropomyosin is responsible for the allergy. It’s found in shellfish as well as in many insects, including cicadas.

The allergic reaction occurs after eating the cicada. Just being around them or handling them won’t trigger a reaction.

Among people with a shellfish allergy, developing a reaction after eating cicadas could be a bigger problem than it seems: up to 10% of people have shellfish allergies and, as noted, insect consumption is common worldwide.

Is it okay for your dog or cat to eat cicadas?

Walking your dog after the emergence of cicadas can be a new and exciting experience for you and your pet! Dogs may chase after cicadas and eat them. Cats might, too, if given the chance. That can be a problem if your pet eats too many, as some will experience stomach upset or other digestive problems.

While the insects are considered harmless to dogs, the American Kennel Club says it’s best to steer them away from cicadas once they’ve eaten a few.

Which other insects trigger allergies?

While insect-related allergic reactions (think bee stings) and infections (like Lyme disease) are well known, the insect-food-allergy connection is a more recent discovery.

One recently recognized condition is the alpha-gal syndrome, in which a person bitten by certain ticks develops an allergy to meat. The name comes from a sugar called galactose-α-1,3-galactose (or alpha-gal) found in many types of meat including beef, lamb, pork, and rabbit. According to the CDC, up to 450,000 people in the US may have developed this condition since 2010.

There aren’t many rigorous studies of the overlap of insects and food allergies, so there are probably others awaiting discovery.

The bottom line

When it comes to eating cicadas, I’ll pass. It’s not because of the risks. I’ve never had a problem with shellfish, and for most people the health risks of eating cicadas seem quite small. It’s just unappealing to me, and I’m not a particularly adventurous eater.

But let’s go easy on those who do enjoy snacking on cicadas. Insects offer a good source of calories and protein. Just because eating them seems unusual in the US doesn’t make it wrong.

So, if you like to eat cicadas and have no shellfish allergy or other reason to avoid them, go for it! This may be a very good summer for you.

About the Author

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Robert H. Shmerling is the former clinical chief of the division of rheumatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), and is a current member of the corresponding faculty in medicine at Harvard Medical School. … See Full Bio View all posts by Robert H. Shmerling, MD

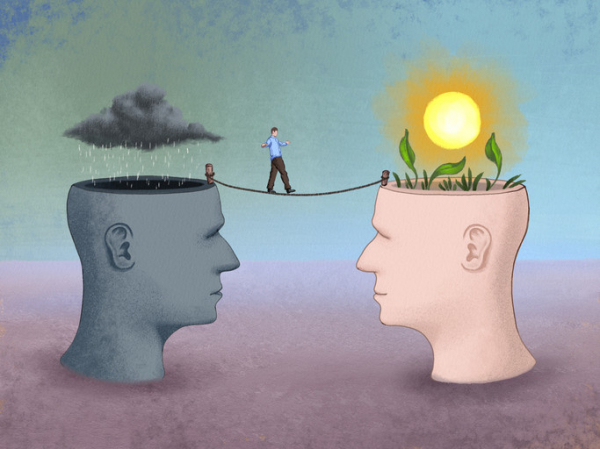

What is cognitive behavioral therapy?

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) teaches people to challenge negative thought patterns and turn less often to unhelpful behaviors. These strategies can improve your mood and the way you respond to challenging situations: a flat tire, looming deadlines, family life ups and downs.

Yet there’s much more depth and nuance to this well-researched form of psychotherapy. It has proven effective for treating anxiety, depression, and other mental health conditions. Tailored versions of CBT can also help people cope with insomnia, chronic pain, and other nonpsychiatric conditions. And it can help in managing difficult life experiences, such as divorce or relationship problems.

What are the key components of CBT?

One important aspect of CBT relates to perspective, says psychologist Jennifer Burbridge, assistant director of the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Program at Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital.

“Therapists who practice CBT don’t see the problems or symptoms people describe as having one single cause, but rather as a combination of underlying causes,” she says. These include

- biological or genetic factors

- psychological issues (your thoughts, physical sensations, and behaviors)

- social factors (your environment and relationships).

Each of these factors contributes to — and helps maintain — the troublesome issues that might prompt you to seek therapy, she explains.

How does CBT describe our emotions?

Our emotions have three components: thoughts, physical sensations, and behaviors.

“Thoughts are what we say to ourselves, or 'self-talk,'” says Burbridge. Physical sensations are what we observe in our bodies when we experience an emotional situation: for example, when your heart rate rises in stressful circumstances. Behaviors are simply the things you do — or do not do. For instance, anxiety might prevent you from attending a social event.

All three components are interrelated and influence one another. That’s why CBT helps people to develop skills in each of them. “Think of it as a wellness class for your emotional health,” says Burbridge.

How long does CBT last?

CBT is a goal-oriented, short-term therapy. Typically it involves weekly, 50-minute sessions over 12 to 16 weeks. Intensive CBT may condense this schedule into sessions every weekday over one to three weeks.

Is CBT collaborative?

“When I first meet with someone, I’ll listen to what’s going on with them and start thinking about different strategies they might try,” Burbridge says. But CBT is a collaborative process that involves homework on the patient’s part.

What might that mean for you? Often, a first assignment involves self-monitoring, noting whether there are certain things, events, or times of day that trigger your symptoms. Future sessions focus on fine-tuning approaches to elicit helpful, adaptive self-talk, and problem-solving any obstacles that might prevent progress.

Certain thinking patterns are often associated with anxiety or depression, says Burbridge. Therapists help people recognize these patterns and then work with patients to find broader, more flexible ways to cope with difficult situations.

“We’re cognitive creatures with big frontal lobes that help us analyze situations and solve problems. That’s useful in some situations. But at other times, when you’re trying to manage your emotions, it may be better to pause and acknowledge and accept your discomfort,” says Burbridge.

Which CBT tools and strategies can help?

That particular skill — paying attention in the present moment without judgement, or mindfulness — is a common CBT tool. Another strategy that’s helpful for anxiety, known as exposure or desensitization, involves facing your fears directly.

“People avoid things that make them nervous or scared, which reinforces the fear,” says Burbridge. With small steps, you gradually expose yourself to the scary situation. Each step provides learning opportunities — for example, maybe you realize that the situation wasn’t as scary as you though it would be.

By trying new things instead of avoiding them, you begin to change your thought patterns. These more adaptive thinking patterns then make it more likely you will try new or challenging experiences in the future, thereby increasing your self-confidence.

How does CBT work?

Brain imaging research suggests conditions like depression or anxiety change patterns of activity in certain parts of the brain. One way CBT may help address this is by modifying nerve pathways involved in fear responses, or by establishing new connections between key parts of the brain.

A 2022 review focused on 13 brain imaging studies of people treated with CBT. The analysis suggested CBT may alter activity in the prefrontal cortex (often called the “personality center”) and the precuneus (which is involved in memory, integrating perceptions of the environment, mental imagery, and pain response).

Who might benefit from CBT?

CBT is appropriate for people of all different ages. This can range from children as young as 3 years — in tandem with parents or caregivers — to octogenarians. In addition to treating anxiety and depression, CBT is also effective for

- eating disorders

- substance abuse

- personality disorders

- attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

Additional evidence shows CBT may help people with different health issues, including irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, insomnia, migraines, and other chronic pain conditions. The therapy may also benefit people with cancer, epilepsy, HIV, diabetes, and heart disease.

“Many medical conditions can limit your activities. CBT can help you adjust to your diagnosis, cope with the new challenges, and still live a meaningful life, despite the limitations,” says Burbridge.

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

Julie Corliss is the executive editor of the Harvard Heart Letter. Before working at Harvard, she was a medical writer and editor at HealthNews, a consumer newsletter affiliated with The New England Journal of Medicine. She … See Full Bio View all posts by Julie Corliss

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Howard LeWine is a practicing internist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Chief Medical Editor at Harvard Health Publishing, and editor in chief of Harvard Men’s Health Watch. See Full Bio View all posts by Howard E. LeWine, MD

Power your paddle sports with three great exercises

On the Gulf Coast of Florida where I live, the telltale sign of summer is not an influx of beachcombers, afternoon storms that arrive exactly at 2 p.m., or the first hurricane warning, but the appearance of hundreds of paddleboarders dotting the inlet waters.

From afar, paddleboarding looks almost spiritual — people standing on nearly invisible boards and gliding across the surface as if walking on water.

But this popular water sport offers a serious workout, just as kayaking and canoeing do. While floating along and casually dipping a paddle in the water may look effortless, much goes on beneath the surface, so to speak.

As warm weather beckons and paddle season arrives, it pays to get key muscles in shape before heading out on the water.

Tuning up muscles: Focus on core, back, arms, and shoulders

“Paddling a kayak, canoe, or paddleboard relies on muscles that we likely haven’t used much during winter,” says Kathleen Salas, a physical therapist with Spaulding Adaptive Sports Centers at Harvard-affiliated Spaulding Rehabilitation Network. “Even if you regularly weight train, the continuous and repetitive motions involved in paddling require endurance and control of specific muscles that need to be properly stretched and strengthened.”

While paddling can be a whole-body effort (even your legs contribute), three areas do the most work and thus need the most conditioning: the core, back, and arms and shoulders.

- Core. Your core comprises several muscles, but the main ones for paddling include the rectus abdominis (that famed “six-pack”) and the obliques, located on the side and front of your abdomen. The core acts as the epicenter around which every movement revolves — from twisting to bending to stabilizing your trunk to generate power.

- Back: Paddling engages most of the back muscles, but the ones that carry the most load are the latissimus dorsi muscles, also known as the lats, and the erector spinae. The lats are the large V-shaped muscles that connect your arms to your vertebral column. They help protect and stabilize your spine while providing shoulder and back strength. The erector spinae, a group of muscles that runs the length of the spine on the left and right, helps with rotation.

- Arms and shoulders: Every paddle stroke engages the muscles in your arms (biceps) and the top of your shoulder (deltoids).

Many exercises specifically target these muscles, but here are three that can work multiple paddling muscles in one move. Add them to your workouts to help you get ready for paddling season. If you haven’t done these exercises before, try the first two without weights until you can do the movement smoothly and with good form.

Three great exercises to prep for paddling

Wood chop

Muscles worked: Deltoids, obliques, rectus abdominis, erector spinae

Reps: 8–12 on each side

Sets: 1–3

Rest: 30–90 seconds between sets

Starting position: Stand with your feet about shoulder-width apart and hold a dumbbell with both hands. Hinge forward at your hips and bend your knees to sit back into a slight squat. Rotate your torso to the right and extend your arms to hold the dumbbell on the outside of your right knee.

Movement: Straighten your legs to stand up as you rotate your torso to the left and raise the weight diagonally across your body and up to the left, above your shoulder, while keeping your arms extended. In a chopping motion, slowly bring the dumbbell down and across your body toward the outside of your right knee. This is one rep. Finish all reps, then repeat on the other side. This completes one set.

Tips and techniques:

- Keep your spine neutral and your shoulders down and back

- Reach only as far as is comfortable.

- Keep your knees no farther forward than your toes when you squat.

Make it easier: Do the exercise without a dumbbell.

Make it harder: Use a heavier dumbbell.

Bent-over row

Muscles worked: Latissimus dorsi, deltoids, biceps

Reps: 8–12

Sets: 1–3

Rest: 30–90 seconds between sets

Starting position: Stand with a weight in your left hand and a bench or sturdy chair on your right side. Place your right hand and knee on the bench or chair seat. Let your left arm hang directly under your left shoulder, fully extended toward the floor. Your spine should be neutral, and your shoulders and hips squared.

Movement: Squeeze your shoulder blades together, then bend your elbow to slowly lift the weight toward your ribs. Return to the starting position. Finish all reps, then repeat with the opposite arm. This completes one set.

Tips and techniques:

- Keep your shoulders squared throughout.

- Keep your elbow close to your side as you lift the weight.

- Keep your head in line with your spine.

Make it easier: Use a lighter weight.

Make it harder: Use a heavier weight.

Superman

Muscles worked: Deltoids, latissimus dorsi, erector spinae

Reps: 8–12

Sets: 1–3

Rest: 30–90 seconds between sets

Starting position: Lie face down on the floor with your arms extended, palms down, and legs extended.

Movement: Simultaneously lift your arms, head, chest, and legs off the floor as high as is comfortable. Hold. Return to the starting position.

Tips and techniques:

- Tighten your buttocks before lifting.

- Don’t look up.

- Keep your shoulders down, away from your ears.

Make it easier: Lift your right arm and left leg while keeping the opposite arm and leg on the floor. Switch sides with each rep.

Make it harder: Hold in the “up” position for three to five seconds before lowering.

About the Author

Matthew Solan, Executive Editor, Harvard Men's Health Watch

Matthew Solan is the executive editor of Harvard Men’s Health Watch. He previously served as executive editor for UCLA Health’s Healthy Years and as a contributor to Duke Medicine’s Health News and Weill Cornell Medical College’s … See Full Bio View all posts by Matthew Solan

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Howard LeWine is a practicing internist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Chief Medical Editor at Harvard Health Publishing, and editor in chief of Harvard Men’s Health Watch. See Full Bio View all posts by Howard E. LeWine, MD